This guide helps family and friends understand the differences between Acute, Recurrent and Chronic urinary tract infections, how chronic infections develop and what treatment options are available.

Chronic or Persistent Urinary tract infections desperately affect the lives of sufferers and it can be difficult for them to explain to you why an infection won’t resolve and their symptoms persist.

What is a UTI?

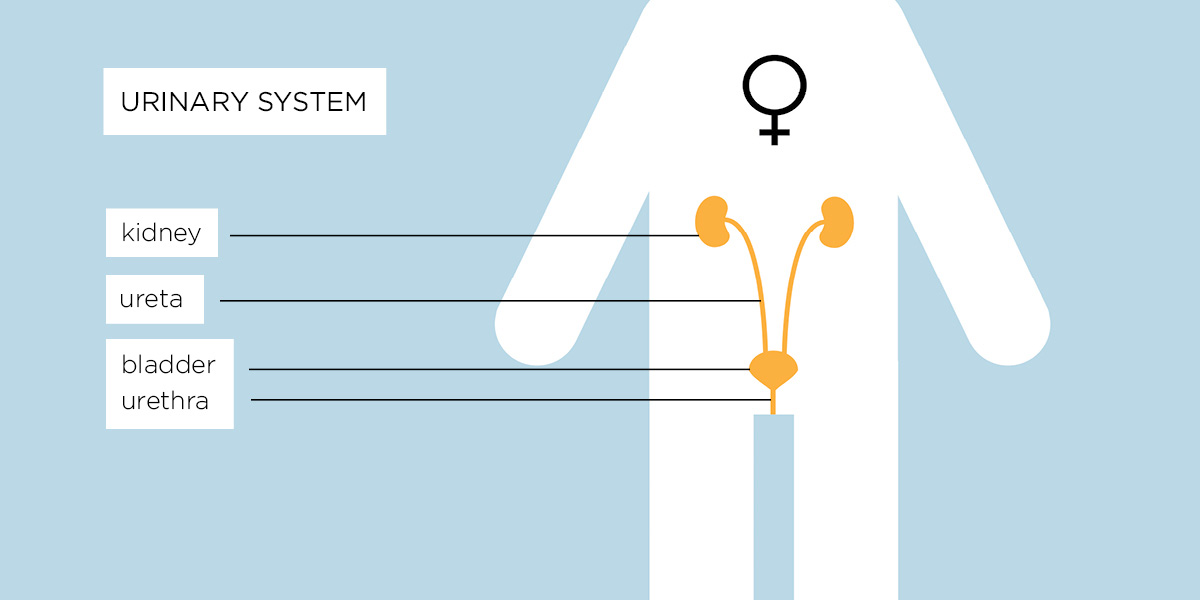

A urinary tract infection (UTI) is an infection of the bladder which is part of the urinary tract (kidneys, bladder and urethra). Cystitis is another name given to a UTI or inflammation of the urinary tract. Its origins are in the Greek terms “cyst,” meaning bladder and “itis,” meaning inflammation. It is one of the most common bacterial infections in the world and an estimated 1 in 3 women suffer a UTI in their lifetime.

Women are more likely to suffer from UTIs, but men and children also get them. There’s not yet enough research to understand why some people never experience a UTI, why some people have only one or two infections and why others develop chronic infections.

A human urinary tract consists of:

- The kidneys – where the urine is produced

- The ureters – there are two ureters, one on each side of the body, and their role is to transport the urine from the kidneys toward the bladder

- The bladder – a sac-like organ which collects the urine produced by the kidneys

- The urethra – a tube through which the urine produced in the kidneys and collected in the bladder is eliminated from the body

Women are more likely to suffer from UTIs, but men and children also get them. There’s not yet enough research to understand why some people never experience a UTI, why some people have only one or two infections and why others develop chronic infections.

Symptoms of a UTI can include:

- A frequent and sometimes pressing urge to pass urine, while only being able to produce small amounts

- A need to pass urine many times a day – this can rise to in excess of 4-6 times an hour on bad days

- Having to get up several times in the night to pass urine, resulting in sleep deprivation

- Pain – usually burning or stinging either in the bladder or urethra – when passing urine

- Cloudy urine or blood in the urine (haematuria)

- A strong, sweet or “fishy” smell to the urine. Bacteria can also change the odour of urine

- Fever, nausea, feeling generally unwell, a dull ache in the lower abdomen. Pain may spread to the back. This latter symptom may mean that the infection has spread to the kidneys

- Pain in the area of the lower abdomen, pubic bone and pelvic floor, with pain often radiating down the legs. Men may also feel pain radiating into the rectum

- Emotional distress and brain fog/confusion. This is especially common in older people with an infection

Acute, recurrent and chronic UTI – how they guide diagnosis and treatment

Infections of the urinary tract can be grouped into 3 types; acute, recurrent and chronic.

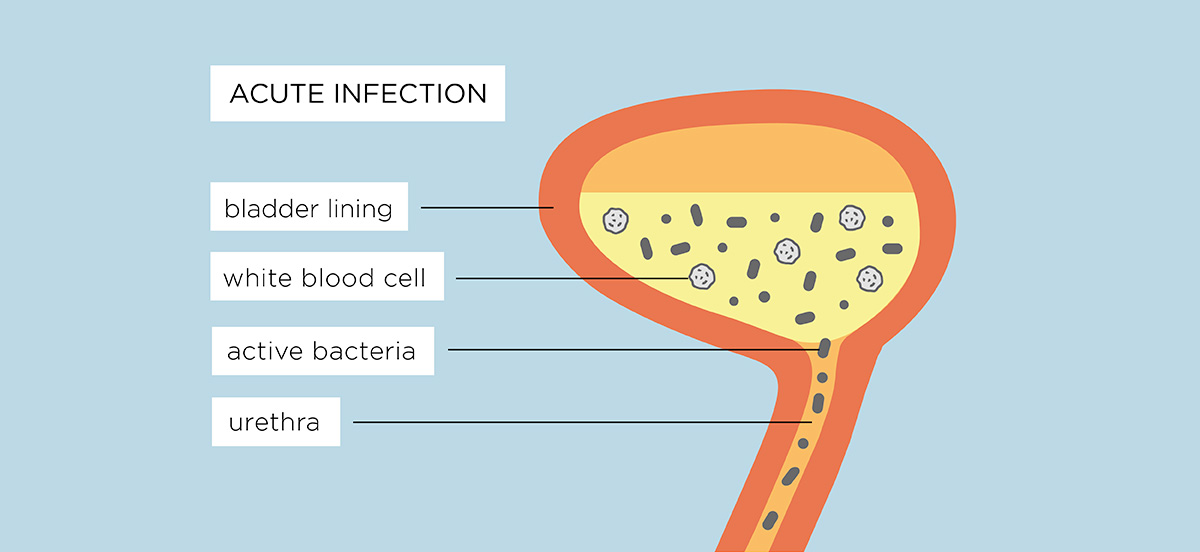

Acute UTI

An acute urinary tract infection is usually seen as a one-off infection that gets better within a few days through antibiotics prescribed by a GP/Primary Care Physician or over the counter treatment options such as cystitis sachets, pain medication and drinking water to flush out the infection.

Recurrent UTI

Recurrent UTI is defined as three episodes of a UTI within a 12 month period or two episodes within the previous six months.

Recurrence usually occurs because the original infection is cleared on treatment with antibiotics but then the same or a different pathogen (infection causing bacteria) gains access to the urinary tract to cause a new infection. This results in another trip to the GP or Emergency room for further antibiotics to clear the infection.

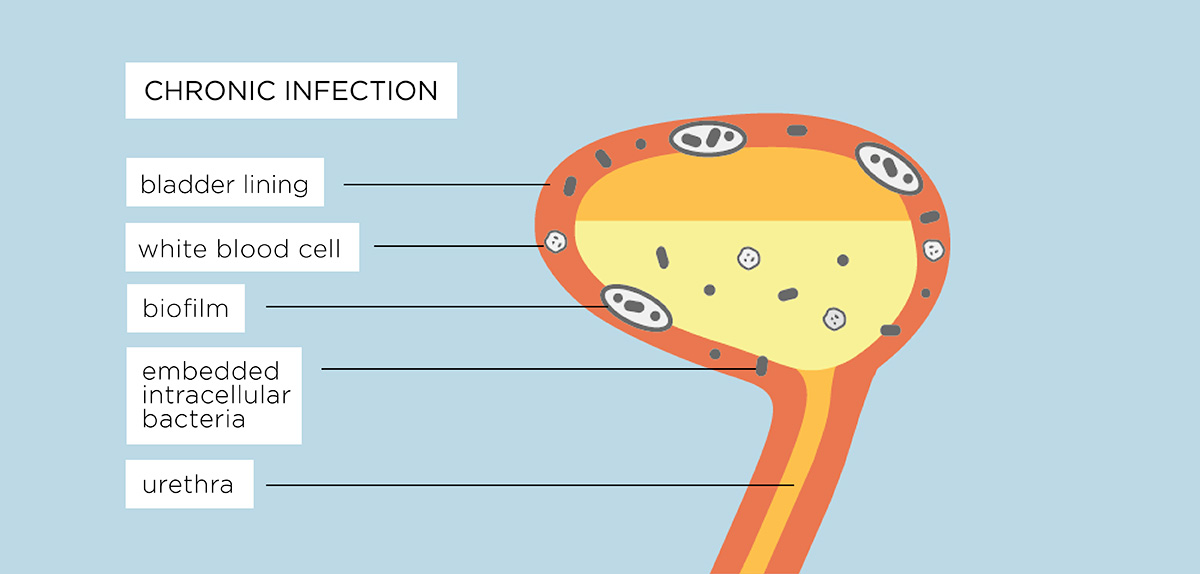

Chronic UTI

Persistent or Chronic UTI occurs when bacteria which caused the original UTI not being completely cleared from the urine and/or bladder wall by initial antibiotic management. It can remain detectable in the urine, and even after further treatment continues to cause symptoms. The sufferer is thus caught in an ongoing cycle of symptoms and treatment. It is this persistence that is called a chronic urinary tract infection or chronic cystitis.

Diagnosis of a UTI

After describing symptoms to a clinician, a dipstick test is done and if the clinician feels it is appropriate, a mid-stream urine sample is taken. The sample may be sent to the laboratory where they culture the urine for bacterial growth. There are problems with these tests however – the dipstick culture misses 60% of chronic UTIs and the culture test misses 90% of chronic UTIs.1, 2

Treatment given for an acute UTI

Suggested treatment might be increasing the intake of water for a few days to flush the bacteria out of the urine, over-the-counter remedies to ease pain or your GP may prescribe antibiotics. These treatment methods can help to resolve an acute attack.

An acute UTI develops into a chronic UTI

An initial infection can clear with antibiotics or self-treatment such as over-the-counter remedies or an increase in water intake, but often a one to three day course of antibiotics isn’t long enough to eliminate infection.3

If the infection reoccurs a few times within a 6-12 month period then the same diagnostic and treatment regime is offered or a course of once daily antibiotic prophylaxis (low dose antibiotics) can be prescribed, particularly if there is a specific trigger such as post coital (sexual intercourse) infections.

A chronic UTI develops when an acute infection is left undiagnosed, untreated or fails to get better with self-treatment or short courses of antibiotics or antibiotic prophylaxis.

Symptoms can return after a few days but because of recent treatment and increased consumption of fluids, the bacteria aren’t detected on further urine sample testing.4, 5

If the infection isn’t diagnosed or properly treated, the bacteria that cause UTIs can move from the urine into the cells of the bladder wall, with the ability to cover themselves with a biofilm. These measures protect them from antibiotics, making them harder to kill and causing a chronic infection.

The infection becomes embedded

A UTI creates inflammation of the bladder wall cells which allows the bacteria to “stick” to the tissues, making them harder to flush out. The bacteria divide, multiply and penetrate the deepest cells of the bladder where they become dormant. This is known as intracellular colonisation. The now dormant pathogenic bacteria irritate the cells and cause inflammation.

Each bacterial cell can also form a biofilm as a protective measure. This is a gooey substance that enables different bacterial microorganisms to join together and grow. Biofilms are already resident in the bladder and other parts of a healthy body – they protect the surface of the eye and the passages of the ear, nose and throat but are also part of conditions like cystic fibrosis or chronic UTI because infection causing bacteria can hide within them.

All this leads to a stand-off in the bladder, with the immune system signalling there is a problem and sending more white blood cells to the inflammed bladder wall cells but because the bacteria are lying dormant, embedded into the bladder wall or within an infectious biofilm, the white blood cells cannot target these bacteria to destroy them. This leads to more pain and inflammatory signals being sent to the brain causing daily symptoms.

Antibiotics cannot kill dormant bacteria

Antibiotics are only effective against dividing microbes outside of the cells and those cells shed into the urine by the immune system fighting the infection. Those dormant bacteria either inside biofilms or embedded in bladder wall cells do not divide. Dormant microbes are known as “persisters” and are resistant to oral antibiotics and aggressive treatment such as intravenous (IV) antibiotics.6

Periodically, these bacteria can wake up, divide vigorously and burst out of either the cells they have colonised or a biofilm. They seek to set up fresh infections in new cells or are shed into the urine by the immune system. Short courses of treatment mean that antibiotics are not always available when this happens. It is these bacterial fluctuations which help to cause the severe symptoms people experience.

Insensitive tests don’t detect infection

Dipstick and urine culture tests are very insensitive and cannot be relied on to detect chronic infection. The dipstick test misses 60% of chronic UTIs and the culture test misses 90% of chronic infections.7, 8

The dipstick test

The dipstick test is very insensitive. Research shows dipsticks have a 70% inaccuracy rate (see also here) causing some to suggest it should be abandoned as a diagnostic tool given it also misses 60% of chronic infections 1, 2 as the diagnostic threshold to confirm a UTI is set at a specific level. This indicator limits the ability of clinicians to consider bacterial infections at lower levels. Dipsticks can also fail to detect white blood cells, a key marker of an infection. They also detect the presence of nitrates but these are only produced by some bacterial pathogens and not others. A negative dipstick result is common even through a patient reports UTI symptoms to their GP.9

You can read more about this test in our factsheet: A guide to Chronic UTI

The culture test misses many pathogens

Research has shown that the culture test detects only 10% of chronic infections.10, 11 The culture test favours the growth of some bacteria and not others. E-coli is often quoted as the most common cause of a UTI as it can be easily grown within an 18-24 hour laboratory test window but UTIs can be caused by other bacteria that either take longer to grow or don’t grow at all, as they die on contact with oxygen. If a single bacteria isn’t grown to a suitable level in the culture test then the patient may be told they have no infection. If bacteria are grown, but are below this agreed diagnostic threshold called the Kass criteria, then the sample is reported as “low growth”, “no growth” or “mixed growth”. If “mixed growth” is shown, the belief is that this is caused by contamination from the vaginal, vulval or anal areas. Additionally it is assumed that only one pathogen – predominantly e-coli – causes infections. But infections can be caused by more than one bacteria from the urinary tract and mixed growth should not be discounted as contamination. However 1 in 4 urine samples are rejected due to contamination.

Many GPs and hospital consultants are unaware that dipstick and culture tests are inaccurate and on the basis of the test results, they deny medication despite their patient showing signs and describing symptoms of a UTI.

The cut-off for infection levels is too high

Clinicians and laboratories globally use a threshold to determine if someone has a UTI. This threshold states that there must be the growth of a single, known UTI-causing bacteria reaching a bacterial colony-forming unit (CFU) of greater than 100,000 CFU (>105) in a millilitre of urine. It is called the Kass criteria, named after a scientist who established this threshold in a 1956 study of pregnant women with severe kidney infections – not urinary tract infections. This threshold is set too high; research has shown that infections are present and cause UTI symptoms and potential kidney damage, at much lower CFU levels.7, 8 This cut-off means that infections under this threshold may not be diagnosed and treated. This applies to both the urine culture and the dipstick test.

No clinician guidelines for chronic UTI

Getting the right diagnosis and treatment to treat chronic infections is absolutely key to recovery. There are currently very few specialists globally who understand what a chronic UTI is. Crucially, GPs and consultants have guidelines for treating acute infections or recurrent infections (where an acute infection occurs more than once in a period of 6-12 months) but there is currently no guidance for diagnosing and treating someone with a chronic infection.

Guidelines for acute or recurrent infections advocate short courses of antibiotics and a reliance on tests results. Insensitive and inaccurate testing often means that the infection is not cleared and a chronic infection develops. Chronic UTI is not recognised by the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) in its guidelines provided to GPs and secondary consultants in the UK for the treatment of UTI and therefore there are no guidelines for this condition. Even with a positive laboratory result, because treatment is based on the management of an acute infection, it will mean a 1-3 day course of antibiotics which can be insufficient to eliminate the infection and symptoms return.

Referral to a specialist

As a result of tests failing to detect infection, GPs may discount bacterial infection as a cause and make a referral to a urologist or urogynaecologist for further investigation to explore other causes. These can include cancer, anatomical issues, pelvic organ prolapse (where one or more of the pelvic organs bulge into or out of the vaginal canal or anus), overactive bladder, prostate problems and bladder or kidney stones. Where there is a family history of urinary tract cancer, it is obviously critical that further investigations are carried out. Some surgical treatments offered by specialists include urethral dilation, bladder stretch, bladder instillations (mixtures of medicines and painkillers put directly into the bladder), botulinum toxin (botox) injected into the bladder or as a last resort, bladder removal. There is no medical evidence proving that these treatments are effective and often they can make someone feel a lot worse.

Sufferers may be offered anti-depressants or pain killers which can dull symptoms but these can sometimes have serious side effects. These include headaches, dizziness, drowsiness and exhaustion, blurred vision, fever, flu symptoms, gastrointestinal problems, weight gain and oedema (fluid retention in parts of the body).

The effects of an untreated infection

Significant health risks can occur when a UTI is not treated including the risk of irreparable kidney damage and urinary sepsis. Bacterial toxins can disrupt normal function. Fatigue, lack of sleep, fever, a sensation of “brain fog” and ongoing sometimes systematic inflammation and pain are some of the symptoms many chronic UTI sufferers experience as a result.

Infection affects sufferers physically and psychologically because of the pain, urgency and frequency of urination, lack of sleep and the effort to avoid all potential triggers that may worsen symptoms. Their quality of life is significantly impacted when they are unable to work, maintain relationships, have families and lead normal, functioning lives. There can be a withdrawal from day-to-day life in order to manage symptoms. You may feel that you do not know how to help or find it difficult to cope with witnessing someone struggle on a daily basis.

Treatment for a chronic UTI

At present, treatments that may be offered include extended courses of full strength antibiotics 14,15,16 the instillation of antibiotics into the bladder where oral antibiotics have failed or are not appropriate, usage of Methenamine Hippurate (Hiprex) or Vaginal Oestrogen therapies.

Extended course oral antibiotics

In a recently published ten-year patient led UK clinical study at the Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Clinic within the Whittington Hospital London22, 624 women were recruited and treated with full dose narrow spectrum, first generation antibiotics alongside the urinary antiseptic Methenamine Hipurate (Hiprex) following unique urine microscopy. This protocol led to a significant reduction of symptoms in 64% of participants with a further 20% feeling very much better. The study noted: “The median number of patient visits was five (mean = 6.6; SD = 5), with 40% of women discharged after four visits and 80% within ten. Mean treatment length was 383 days. Some patients required long-term therapy, as attempts to withdraw treatment were associated with relapse. Others were treated successfully but requested long-term monitoring due to anxieties about disease recurrence”.

Antibiotic bladder instillations

Antibiotic bladder instillations may be a treatment of last resort considered by clinicians for patients who either have major systemic side effects using oral antibiotics, poor outcome from their use or require a localised rather than oral route.

Patients undergoing renal transplants and those with spinal injuries and neuropathic/neurogenic bladders often have major issues with UTI. They can have much higher rates of UTI than the general population. Catheter usage can cause the formation of biofilms.

However at present, it should be noted that there are no large randomised control studies to demonstrate long term efficacy for the management of chronic urinary tract infections using bladder instillations and there are no standardised treatment regimes – instillations in trials have been offered daily for a week, every third day or once a week.

Antibiotic instillations should not be confused with bladder GAG layer instillations where the aim is to repair the outer GAG layer of the bladder wall for those patients diagnosed with Interstitial Cystitis. If offered this treatment pathway, check that the specialist makes clear what is the make up of the instillation in case it is a GAG layer treatment rather than an antibiotic therapy.

Methenamine Hippurate or Hiprex

Hiprex is not an antibiotic but a urinary antiseptic originally developed and licensed in the 1960s. This means there is little risk of pathogenic bacteria developing resistance.

- Hiprex is often prescribed alongside antibiotics or on its own.

- If an infection has significantly improved and antibiotics are no longer required on a daily basis, Hiprex is often prescribed as an ongoing treatment to prevent infections reoccurring.

- Hiprex can be taken during pregnancy under clinician management.

The active ingredient is methenamine hippurate. It has antibacterial activity because the methenamine component is broken down to formaldehyde and ammonia in acid urine. By converting to bactericidal formaldehyde it prevents bacterial growth by destroying the proteins and replication abilities within a bacterium

The key to the effectiveness of Hiprex is maintaining concentrated, acid urine so that the main ingredients are activated. If the urine is too dilute and alkaline with a urinary PH of over 6.0, Hiprex will be ineffective. Some people find that taking Hiprex with vitamin C can help to maintain an acid urine balance but this is by personal choice and is not essential to the activation of Hiprex.

In December 2024, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the UK, gave approval to GPs and secondary consultants in updated guidelines for the usage of Hiprex as a prescribed alternate to daily antibiotic prophylaxis for those with recurrent UTI that has not been adequately improved by behavioural and personal hygiene measures, vaginal oestrogen or single-dose daily antibiotic prophylaxis (if any of these have been appropriate and are applicable). They noted that a review of treatment with methenamine hippurate should occur within 6 months, and then every 12 months, or earlier if agreed with the patient.

Localised Oestrogen Therapies

Oestrogen (or estrogen) is needed for the vagina to maintain its natural flora and lubrication. Declining oestrogen levels during the peri and menopausal years leads to changes to vaginal PH increasing alkalinity. This matters because an acidic vaginal environment is protective. It creates a barrier that prevents unhealthy bacteria and yeast from multiplying too quickly and causing infection. Thus a high vaginal pH level — above 4.5 — provides the perfect environment for unhealthy bacteria to grow and these bacteria can transfer from the vagina to the urinary tract causing ongoing infection problems.

A study published in Science Translational Medicine in 2013 23 noted that oestrogen also encourages production of natural antimicrobial substances in the bladder. The hormone also makes the epithelium of the bladder stronger by closing the gaps between cells that line the bladder wall. By “gluing” together the cells of the bladder wall, it helps to prevent bacteria from penetrating to the deeper layers of the wall. Conversely it will also help prevent too many cells from shedding from the top layers of the bladder wall thus preventing exposure of the deeper bladder wall tissues to bacteria. A study carried out by the University of Texas at the European Association of Urology Congress in 2020 24 showed that for some women who took hormone replacement therapies, they had a greater variety of beneficial bacteria in their urine, possibly creating conditions that discourage urinary infections.

For localised oestrogen treatment for the urogenital tract, pessaries have been found to be beneficial. They are entirely topical and will treat the vagina and bladder with minimal systemic absorption although some women still report symptoms despite the low dosage.

Topical oestrogen creams are also available for use in the vagina and vulval area. If skin is highly sensitive, then discuss their usage with the prescribing specialist as the additives within some creams can cause inflammation and burning. A small patch test may be the best option if considering using a cream.

Find Chronic UTI Practitioners in the UK & US

How can I help?

The isolation of a chronic urinary tract infection can be emotionally and physically crippling due to the pain, anxiety and exhaustion of managing symptoms daily. A chronic UTI sufferer may have to stay in bed, be housebound and in severe pain. It is very difficult it is for sufferers to have the confidence to talk to family or friends about what they are going through. Some are so embarrassed they feel they can’t tell people – even those close to them.

Friends and family can help in the following ways:

- Try to help to lessen the immediate pressure of the day-to-day task load, talk amongst family and friends and build a plan to help.

- Make them feel supported, not isolated, in all they are going through.

- Your family member or friend is often grieving for what they have had to give up whilst unwell and this affects them both emotionally and physically. Some have talked about suicide. They may not feel able to communicate this so let them talk and express their fears and emotions. If your friend or family member can’t cope, counselling should be considered. Contact an appropriate organisation or their GP if you have concerns for their safety.

- The bacterial infection can cause acute symptoms for a period of time, resolve and then flare up again. People refer to these periods as “flares”. They often occur when bacteria are released from the bladder wall and symptoms increase. When this happens, encourage them to contact their specialist. Flares can last days or weeks but they do eventually resolve with treatment.

- If appropriate, go to their medical appointments with them. Often someone cannot ask the right questions in their consultation, especially when they are unwell and you may be able to help them.

- Work together to prepare a list of questions in advance and make sure that all of them are answered before you leave the appointment.

- Be aware that because the tests that clinicians rely on may offer a false-negative result, chronic UTI sufferers have had experience of clinicians suggesting that symptoms are psychosomatic and that the sufferer is imagining them or exaggerating their condition. Supporting someone at their appointment will reinforce the message that this illness is not imagined.

- Face up to this illness. Sufferers have described how families and friends have frequently made them feel excluded, feel guilty about what they are going through or simply denied their illness is as bad as they describe.

- No-one wishes to discuss wee but chronic UTI exists and friends and family must advocate for loved ones to help them and also help others get better diagnostics and treatment. It is more common than you think. 1.7 million people in the UK suffer from Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms 17 and between 25–35 percent of patients treated according to guidelines for acute UTI fail treatment (whether prescribed antibiotics for 3 or 14 days).18

- Don’t take a lack of physical intimacy with your partner personally. A chronic UTI causes severe pain in the pelvic area as well as the bladder and urethra. Intercourse can often be too painful to attempt or can cause a flare up of symptoms. Sufferers are not rejecting you – they desperately want to be “normal”. Whilst difficult, supporting your partner by having an honest and open discussion throughout their treatment will help and some sufferers and their partners have found counselling to be of benefit.

Don’t suggest:

- Cranberry juice. This doesn’t work. Research studies19,20,21 have proven that it is not effective in treating infections. Indeed it is often full of sugar and very acidic which provides some bacteria with an environment in which to multiply, as well as increasing inflammation and pain.

- That the symptoms they feel are exaggerated or in their heads. A chronic illness does not have to manifest itself in an immediately obvious physical way. The self-esteem and confidence of sufferers is an integral part of their healing. Anxiety about how they are perceived can often debilitate a sufferer and stop them from having the strength to work on healing.

Other Factsheets also available:

A Chronic UTI Information Sheet for GPs

An Employer’s Guide to Chronic UTI

For further information and support visit:

The Chronic Urinary Tract Infection Campaign

References:

1 Mambatta AK, Jayarajan J, Rashme VL, Harini S, Menon S, Kuppusamy J. Reliability of dipstick assay in predicting urinary tract infection. J Family Med Prim Care. 2015 Apr-Jun;4(2):265-8. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.154672. PMID: 25949979; PMCID: PMC4408713.

Little P, Turner S, Rumsby K, Jones R, Warner G, Moore M, Lowes JA, Smith H, Hawke C, Leydon G, Mullee M. Validating the prediction of lower urinary tract infection in primary care: sensitivity and specificity of urinary dipsticks and clinical scores in women. Br J Gen Pract. 2010 Jul;60(576):495-500. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X514747. PMID: 20594439; PMCID: PMC2894378.

2 Sathiananthamoorthy, S., et al., Reassessment of Routine Midstream Culture in Diagnosis of Urinary Tract Infection. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 2018.

Gill, K., et al., A blinded observational cohort study of the microbiological ecology associated with pyuria and overactive bladder symptoms. Int Urogynecol J, 2018.

3. Ross A. Lawrenson, John W. Logie, Antibiotic failure in the treatment of urinary tract infections in young women, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, Volume 48, Issue 6, December 2001, Pages 895–901, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/48.6.895

4. Price TK, Dune T, Hilt EE, Thomas-White KJ, Kliethermes S, Brincat C, et al. The clinical urine culture: enhanced techniques improve detection of clinically relevant microorganisms. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(5):1216–22

5. Wolfe AJ, Toh E, Shibata N, Rong R, Kenton K, Fitzgerald M, et al. Evidence of uncultivated bacteria in the adult female bladder. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(4):1376–83

6. Wood, T., Knabel, S., Kwan, B., Bacterial Persister Cell Formation and Dormancy. Applied and Environmental Microbiology Nov 2013, 79 (23) 7116-7121; DOI: 10.1128/AEM.02636-13

7. Sathiananthamoorthy, S., et al., Ibid

8. Gill et all. Ibid

9. Mambatta AK, Jayarajan J, Rashme VL, Harini S, Menon S, Kuppusamy J. Reliability of dipstick assay in predicting urinary tract infection.J Family Med Prim Care. 2015;4(2):265–268. doi:10.4103/2249-4863.154672

10. Sathiananthamoorthy, S., et al., Ibid

11. Gill et all. Ibid

12. Theodoros A. Kanellopoulos, Paul J. Vassilakos, Marinos Kantzis, Aikaterini Ellina, Fevronia Kolonitsiou, Dimitris A. Papanastasiou. Low bacterial count urinary tract infections in infants and young children. Eur J Pediatr (2005) 164: 355–361 DOI 10.1007/s00431-005-1632-0 13. Kjell Tullus, Low urinary bacterial counts: do they count? Pediatr Nephrol (2016) 31:171–174 DOI 10.1007/s00467-015-3227-y

14. Lebeaux D, Ghigo JM, Beloin C. Biofilm-Related Infections: Bridging the Gap between Clinical Management and Fundamental Aspects of Recalcitrance toward Antibiotics. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews Sep 2014, 78 (3) 510-543; DOI: 10.1128/MMBR.00013-14

15. Swamy, S., Barcella, W., De Iorio, M., Gill, K., Rajvinder, K., Kupelian, A., Rohn, J., Malone-Lee, J. Recalcitrant chronic bladder pain and recurrent cystitis but negative urinalysis. What should we do? Int Urogynecol J (2018) 29: 1035

16. Swamy, S., Kupelian, A., Rajvinder, K., Dharmasena, D., Toteva, H., Dehpour, T., Collins, L., Rohn, J., Malone-Lee, J. Cross-over data supporting long-term antibiotic treatment in patients with painful lower urinary tract symptoms, pyuria and negative urinalysis Int Urogynecol J (2018) IUJO-D-18-00488R1

17. UK figures based on Rand Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology Study 2010

18. Price TK, Dune T, Hilt EE, Thomas-White KJ, Kliethermes S, Brincat C, et al. The clinical urine culture: enhanced techniques improve detection of clinically relevant microorganisms. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(5):1216–22

Ross A. Lawrenson, John W. Logie, Antibiotic failure in the treatment of urinary tract infections in young women, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, Volume 48, Issue 6, December 2001, Pages 895–901, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/48.6.895

19. Jepson RG, Williams G, Craig JC. Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 10. Art. No.: CD001321. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001321.pub5.

20. Jepson RG, Mihaljevic L, Craig JC. Cranberries for treating urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1998, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD001322. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001322.

21. Gunnarsson AK, Gunningberg L, Larsson S, Jonsson KB. Cranberry juice concentrate does not significantly decrease the incidence of acquired bacteriuria in female hip fracture patients receiving urine catheter: a double-blind randomized trial. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:137–143. Published 2017 Jan 13. doi:10.2147/CIA.S113597

22. Swamy, S., Barcella, W., De Iorio, M. et al. Recalcitrant chronic bladder pain and recurrent cystitis but negative urinalysis: What should we do?. Int Urogynecol J 29, 1035–1043 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3569-7

23. Petra Lüthje et a. Estrogen Supports Urothelial Defense Mechanisms.Sci. Transl. Med.5,190ra80-190ra80(2013).DOI:10.1126/scitranslmed.3005574

24. Neugent ML, Kumar A, Hulyalkar NV, Lutz KC, Nguyen VH, Fuentes JL, Zhang C, Nguyen A, Sharon BM, Kuprasertkul A, Arute AP, Ebrahimzadeh T, Natesan N, Xing C, Shulaev V, Li Q, Zimmern PE, Palmer KL, De Nisco NJ. Recurrent urinary tract infection and estrogen shape the taxonomic ecology and function of the postmenopausal urogenital microbiome. Cell Rep Med. 2022 Oct 18;3(10):100753. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100753. Epub 2022 Sep 30. PMID: 36182683; PMCID: PMC9588997.