This guide helps understand the differences between Acute, Recurrent and Chronic urinary tract infections, how chronic infections develop and what treatment options are available.

What is a UTI?

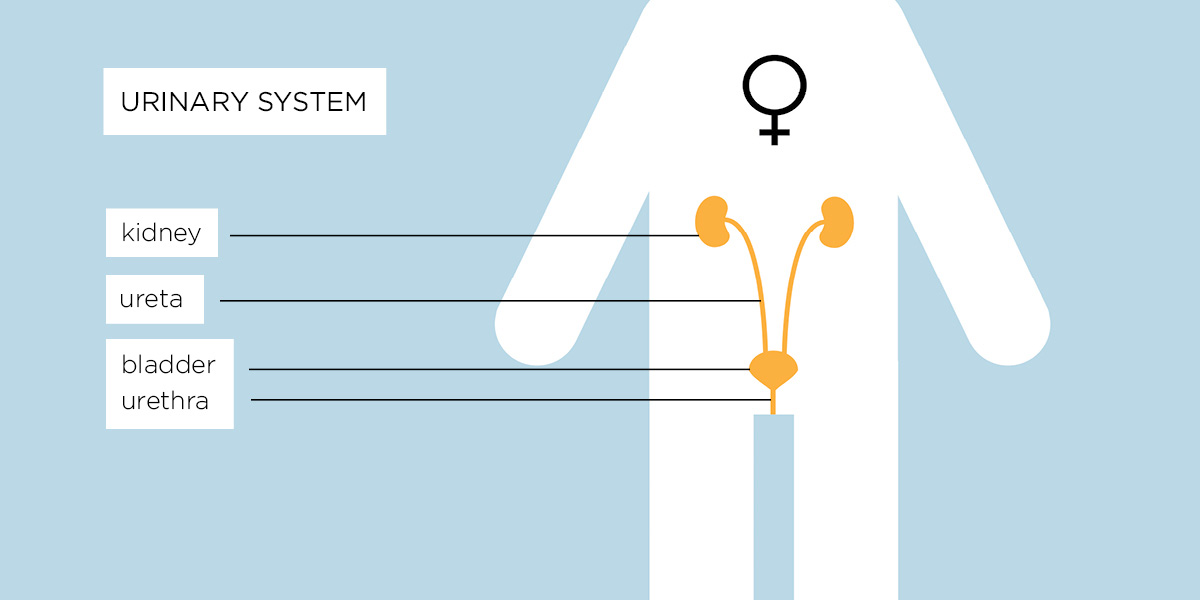

A urinary tract infection (UTI) is an infection of the bladder which is part of the urinary tract (kidneys, bladder and urethra). Cystitis is another name given to a UTI or inflammation of the urinary tract. Its origins are in the Greek terms “cyst,” meaning bladder and “itis,” meaning inflammation. It is one of the most common bacterial infections in the world and an estimated 1 in 3 women suffer a UTI in their lifetime.

Women are more likely to suffer from UTIs, but men and children also get them. There’s not yet enough research to understand why some people never experience a UTI, why some people have only one or two infections and why others develop chronic infections.

A human urinary tract consists of:

- The kidneys – where the urine is produced

- The ureters – there are two ureters, one on each side of the body, and their role is to transport the urine from the kidneys toward the bladder

- The bladder – a sac-like organ which collects the urine produced by the kidneys

- The urethra – a tube through which the urine produced in the kidneys and collected in the bladder is eliminated from the body

Women are more likely to suffer from UTIs, but men and children also get them. There’s not yet enough research to understand why some people never experience a UTI, why some people have only one or two infections and why others develop chronic infections.

What can cause a UTI?

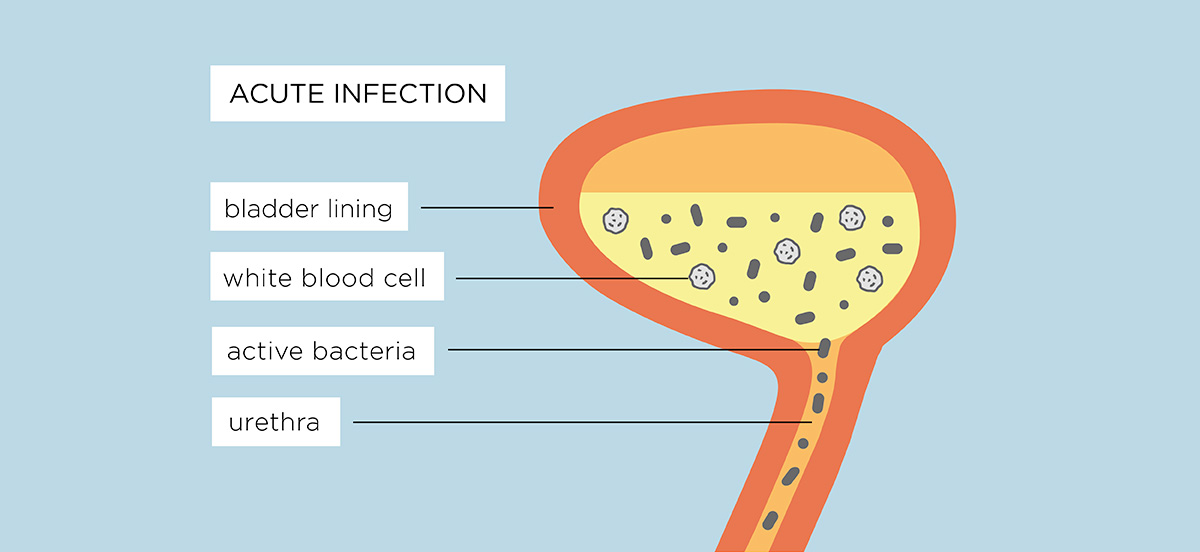

A UTI usually occurs when infection-causing bacteria are introduced via the urethra into the bladder or due to an upsurge of infection-causing bacteria in the bladder or urethra.

A UTI can also result from other issues including catheter use, structural abnormality of the urinary tract and neurological conditions that prevent a person from emptying their bladder such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes or spinal injury.

Symptoms of a UTI

Someone suffering from a UTI may experience some or all of these symptoms:

- A frequent and sometimes pressing urge to pass urine, while only being able to produce small amounts

- A need to pass urine many times a day – this can rise to in excess of 4-6 times an hour on bad days

- Having to get up several times in the night to pass urine, resulting in sleep deprivation

- Pain – usually burning or stinging either in the bladder or urethra – when passing urine

- Cloudy urine or blood in the urine (haematuria)

- A strong, sweet or “fishy” smell to the urine. Bacteria can also change the odour of urine

- Fever, nausea, feeling generally unwell, a dull ache in the lower abdomen. Pain may spread to the back. This latter symptom may mean that the infection has spread to the kidneys

- Pain in the area of the lower abdomen, pubic bone and pelvic floor, with pain often radiating down the legs. Men may also feel pain radiating into the rectum

- Emotional distress and brain fog/confusion. This is especially common in older people with an infection

Acute, recurrent and chronic UTI – how they guide diagnosis and treatment

Infections of the urinary tract can be grouped into 3 types; acute, recurrent and chronic.

Acute UTI

An acute urinary tract infection is usually seen as a one-off infection that gets better within a few days through antibiotics prescribed by a GP/Primary Care Physician or over the counter treatment options such as cystitis sachets, pain medication and drinking water to flush out the infection.

Recurrent UTI

Recurrent UTI is defined as three episodes of a UTI within a 12 month period or two episodes within the previous six months.

Recurrence usually occurs because the original infection is cleared on treatment with antibiotics but then the same or a different pathogen (infection causing bacteria) gains access to the urinary tract to cause a new infection. This results in another trip to the GP or Emergency room for further antibiotics to clear the infection.

Chronic UTI

Persistent or Chronic UTI occurs when bacteria which caused the original UTI not being completely cleared from the urine and/or bladder wall by initial antibiotic management. It can remain detectable in the urine, and even after further treatment continues to cause symptoms. The sufferer is thus caught in an ongoing cycle of symptoms and treatment. It is this persistence that is called a chronic urinary tract infection or chronic cystitis.

Diagnosis of a UTI

Diagnosis for a urinary infection is usually done in the GP surgery or a walk-in clinic. After you explain your symptoms, you will be asked to provide a urine sample and a dipstick test is carried out on the sample to check for:

White blood cells

This indicates that there is inflammation or infection in the urinary tract or kidneys and the body is excreting more white blood cells to destroy any possible bacterial infection.

Red blood cells

The bladder can bleed due to severe inflammation and the constant urination caused by a UTI. Some people can feel a “razor blade sensation” when urinating during a UTI attack.

Protein

The presence of protein can indicate a possible kidney infection as only trace amounts normally filter through the kidneys.

Nitrates

Gram-negative bacteria like e-coli, which can cause a UTI, make an enzyme that changes waste urinary nitrates to nitrites.

Any sign of these in the urine on a dipstick test indicates bladder inflammation and a probable infection as the body’s immune system is reacting to the infection, but could also indicate other clinical conditions1. Depending on the dipstick analysis, the GP may send the sample to a laboratory for further analysis. The GP will discuss your symptoms with you, taking into account other current or previous health issues and any family disease history.

Common treatments for a UTI

If symptoms are acute and noticeable blood, protein and nitrates are found via the dipstick test, you may be given a course of between one and three days of antibiotics.

If symptoms are not severe or the dipstick result is negative – highly likely for those with chronic UTI, as the dipstick test detects only 40% of chronic infections – GPs may advise to use over-the-counter cystitis relief sachets, pain relief, cranberry juice and to drink plenty of water. However research shows that cranberry juice is ineffective.2, 3, 4

If your sample has been sent for culture and shows bacterial infection, the GP will prescribe antibiotics or change the antibiotic given to you if the report shows that the bacteria is not sensitive to the antibiotic you are taking. However, the laboratory culture will grow only certain fast-growing bacteria such as E-coli in the 24 hour timeframe for analysis whilst other slow-growth pathogens go undetected.

An acute UTI develops into a chronic UTI

An initial infection may resolve with antibiotics or self-treatment like over-the-counter remedies or an increase in water intake, but often a one to three day course of antibiotics isn’t long enough to eliminate infection. A chronic UTI develops when an acute infection is left undiagnosed, untreated or fails to get better with self-treatment or short courses of antibiotics.

Symptoms can return after a few days but because of recent treatment and increased consumption of fluids, the bacteria aren’t detected on further urine sample testing.

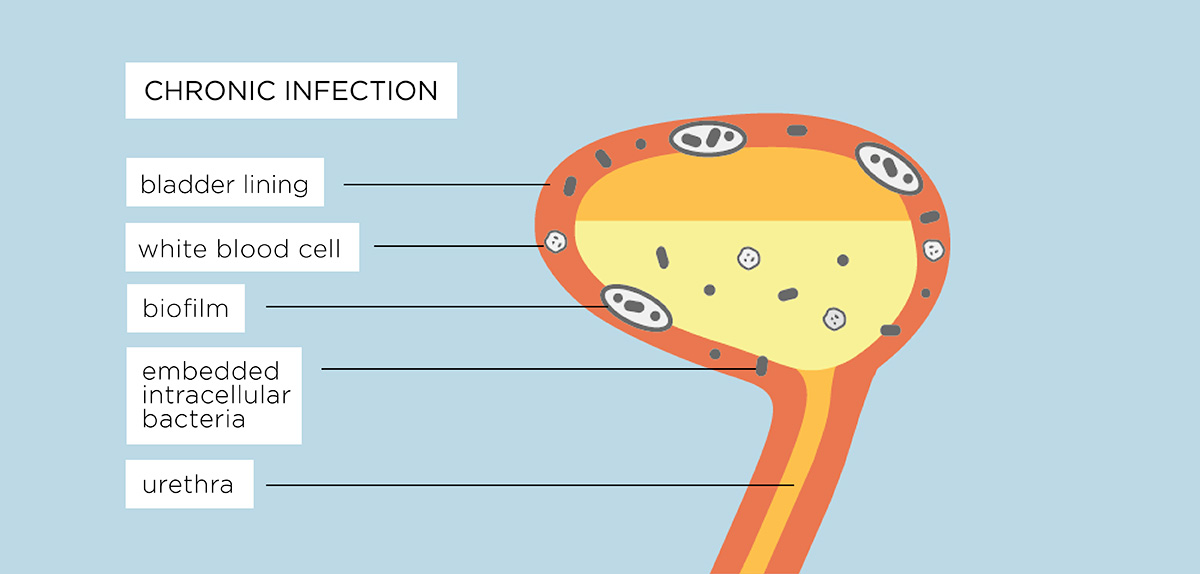

If the infection isn’t diagnosed or appropriately treated, the bacteria that cause UTIs can move from the urine into the cells of the bladder wall, becoming embedded. The bacteria can also cover themselves with a biofilm.5-6. These measures protect them from antibiotics, making them harder to kill and causing a chronic infection.

The infection becomes embedded

A UTI creates inflammation of the bladder wall cells which allows the bacteria to “stick” to the tissues, making them harder to flush out. The bacteria divide, multiply and penetrate the deepest cells of the bladder where they become dormant. This is known as intracellular colonisation. The now dormant pathogenic bacteria irritate the cells and cause inflammation.

Each bacterial cell can also form a biofilm as a protective measure. This is a gooey substance that enables different bacterial microorganisms to join together and grow. Biofilms are already resident in the bladder and other parts of a healthy body – they protect the surface of the eye and the passages of the ear, nose and throat but are also part of conditions like cystic fibrosis or chronic UTI because infection causing bacteria can hide within them.

All this leads to a stand-off in the bladder, with the immune system signalling there is a problem and sending more white blood cells to the inflammed bladder wall cells but because the bacteria are lying dormant, embedded into the bladder wall or within an infectious biofilm, the white blood cells cannot target these bacteria to destroy them. This leads to more pain and inflammatory signals being sent to the brain causing daily symptoms.

Antibiotics cannot kill dormant bacteria

Antibiotics are only effective against dividing microbes outside of the cells and those cells shed into the urine by the immune system fighting the infection. Those dormant bacteria either inside biofilms or embedded in the bladder wall cells do not divide. Dormant microbes are known as “persisters” and are resistant to oral antibiotics and aggressive treatment such as intravenous (IV) antibiotics.7

Periodically, these bacteria can wake up, divide vigorously and burst out of either the cells they have colonised or a biofilm. They seek to set up fresh infections in new cells or are shed into the urine by the immune system. Short courses of treatment mean that antibiotics are not always available when this happens. It is these bacterial fluctuations which help to cause the severe symptoms people experience.

Insensitive tests don’t detect infection

Dipstick and urine culture tests are very insensitive and cannot be relied on to detect chronic infection. The culture misses 90% of chronic UTIs and the dipstick test misses 60% of chronic UTIs.8, 9 Over 50 peer-reviewed papers, spanning 35 years, highlight the unreliability of the tests. 10-30

The dipstick test

Negative dipstick analysis is common even though a patient reports UTI symptoms to their GP. Research shows dipsticks have a 70% inaccuracy rate (see also here) causing some to suggest it should be abandoned as a diagnostic tool. Indeed for those with chronic cystitis, the dipstick only detects 40% of such infections.8, 9 This can be because:

- Dipsticks are calibrated to detect white blood cells counts of greater than 100,000 (>105) bacteria per millilitre of urine or greater. This arbitrary marker (called the Kass criteria) is set too high and is based on a study in 1956 of pregnant women with kidney infections. Patients can have bacterial infections much lower than this threshold however the dipstick will report a “false negative” and they can be denied medication.31, 32

- A current or recently-finished course of antibiotics will reduce bacterial growth leading to no evidence of infection when dipped.

- Drinking too much liquid before providing a sample will dilute it meaning less bacteria in the urine when tested with a dipstick.

- Bacteria require a minimum of four hours to reduce the nitrate to nitrite and not all bacteria responsible for UTIs contain nitrate reductase, the enzyme responsible for this conversion. Examples of Nitrate reducing bacteria including E-coli, Proteus and Klebsiella. These are known as Gram-Negative bacteria. This dipstick marker does not exclude infection as it does not detect gram-positive bacteria that may be causing the infection.

- Bacteria embedded in the cells of the bladder wall or those surrounded by a biofilm cannot be detected by a dipstick test. It can only detect bacteria free floating in the urine.

The culture test

Research has shown that the culture test misses 90% of chronic infections.8, 9 It favours the growth of some bacteria and not others and the high threshold level for bacterial growth to confirm infection means that many patients are misdiagnosed as being negative for a UTI. Reasons include:

- E-coli bacteria is often quoted as the most common cause of a UTI, however it is a fast-growing bacteria that can be easily grown within an 18-24 hour laboratory test period. UTIs can be caused by other bacteria that either take longer to grow or don’t grow at all as they die on contact with oxygen.

- If a single bacteria isn’t grown to an agreed clinical threshold level in the laboratory test, then you may be told you have no infection. However, UTI symptoms can be caused by low levels of pathogens that fall below this threshold, so the lab report will read as negative for infection. At present, laboratory analysis detects as little as 12% of other clinically-significant species that can cause UTI symptoms.33

- If bacteria are grown, but are below this agreed diagnostic clinical threshold then you may be told your sample is of “low growth” or “no growth” or “mixed growth”. If “mixed growth” is shown, a patient is likely to be told that this is caused by contamination from the vaginal or vulval area but in fact may be slow-growing microbes from the bladder. 1 in 4 samples are rejected due to contamination. Chronic infections are now known to be caused by more than one bacterial pathogen and mixed growth should not be discounted as contamination.

- The E. coli focused design of a standard culture could explain our current E. coli centric view of UTI we have today, since so many other organisms remain undetected. Indeed in one study that analysed 157,000 urine samples using a different technology, E.coli was the dominant species in only 28% of cases.

- The threshold for leukocytes in a urine culture (which was established even earlier than the SUC itself) is too high as it does not take into consideration leukocyte deterioration during storage. White blood cells, a key marker of infection degrade in the urine after two hours. If the sample is not stored properly at the GP surgery or sent to the laboratory within this timeframe, the sample may be rejected or a false negative reported.

- Bacteria show up less frequently on tests once they become embedded in biofilm or become embedded inside intracellular reservoirs.

The bladder is not sterile

Recent studies 34-38 show that the bladder has a viable microbial community in the same way that the gut has. But there is still a held belief that the bladder and urine are sterile and bacteria are introduced via the urethra causing infection. Recent research disproves the theory of the sterile bladder – it is now known that the bladder microbiome is home to over 400 different microbes including bacteria and viruses.

Little GP awareness of testing problems

Many GPs are unaware that dipstick and culture tests are inaccurate and on the basis of the results, deny medication to patients despite deny medication to patients despite them presenting with clear clinical signs and symptoms of a UTI.

With false-negative test results, GPs often discount bacterial infection as a cause and may refer patients to a specialist such as a urologist or urogynaecologist for further investigation to explore other causes.

Seeing a consultant

A consultant at a hospital (secondary care) will look for possible causes of urinary symptoms that aren’t explained by infection. These can include anatomical issues, pelvic organ prolapse, overactive bladder, prostate problems, bladder or kidney stones and cancer. Where there is a familial history of urinary tract cancer, it is obviously critical that further investigations are carried out.

Secondary care treatments offered

Some surgical treatments offered by specialists include urethral dilation, bladder stretch, bladder instillations (mixtures of medicines, painkillers or botulinum toxin/ Botox put directly into the bladder) or as a last resort, bladder removal. There is no medical evidence proving that these treatments are effective and often they can make someone feel a lot worse.

You may also be offered anti-depressants or pain killers which can dull down symptoms but these can sometimes have serious side effects which include headaches, dizziness, drowsiness and exhaustion, blurred vision, fever, flu symptoms, gastro-intestinal problems, weight gain and oedema (fluid retention in parts of the body).

Why can’t a doctor treat a chronic UTI?

GPs and consultants have guidelines for treating acute infections or recurrent infections (where an acute happens more than once in a period of 6-12 months) but there is currently no guidance for diagnosing and treating someone with a chronic infection.

There is also significant pressure on GPs to limit the prescription of antibiotics to short courses or low dosages because of concern about anti-microbial resistance (AMR). In the case of recurrent and chronic UTIs a short course or a low-dose isn’t enough to kill all the pathogenic bacteria and they become resistant to antibiotics, fuelling AMR and resulting in a return or the constant presence of symptoms.

Treatment for a chronic UTI

It is only in recent years that research has revealed more about bacteria in the urinary tract and how a UTI can become a chronic infection.39-45 There are now global research centres focusing on the urinary microbiome and urinary tract infections including the development of future treatments.

At present, treatments that may be offered include extended courses of full strength antibiotics, the instillation of antibiotics into the bladder where oral antibiotics have failed or are not appropriate, usage of Methenamine Hippurate (Hiprex) or Vaginal Oestrogen therapies.

Extended course oral antibiotics

In a recently published ten-year patient led UK clinical study at the Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Clinic within the Whittington Hospital London46, 624 women were recruited and treated with full dose narrow spectrum, first generation antibiotics alongside the urinary antiseptic Methenamine Hipurate (Hiprex) following unique urine microscopy. This protocol led to a significant reduction of symptoms in 64% of participants with a further 20% feeling very much better. The study noted: “The median number of patient visits was five (mean = 6.6; SD = 5), with 40% of women discharged after four visits and 80% within ten. Mean treatment length was 383 days. Some patients required long-term therapy, as attempts to withdraw treatment were associated with relapse. Others were treated successfully but requested long-term monitoring due to anxieties about disease recurrence”.

Antibiotic bladder instillations

Antibiotic bladder instillations may be a treatment of last resort considered by clinicians for patients who either have major systemic side effects using oral antibiotics, poor outcome from their use or require a localised rather than oral route.

Patients undergoing renal transplants and those with spinal injuries and neuropathic/neurogenic bladders often have major issues with UTI. They can have much higher rates of UTI than the general population. Catheter usage can cause the formation of biofilms.

However at present, it should be noted that there are no large randomised control studies to demonstrate long term efficacy for the management of chronic urinary tract infections using bladder instillations and there are no standardised treatment regimes – instillations in trials have been offered daily for a week, every third day or once a week.

Antibiotic instillations should not be confused with bladder GAG layer instillations where the aim is to repair the outer GAG layer of the bladder wall for those patients diagnosed with Interstitial Cystitis. If offered this treatment pathway, check that the specialist makes clear what is the make up of the instillation in case it is a GAG layer treatment rather than an antibiotic therapy.

Methenamine Hippurate or Hiprex

Hiprex is not an antibiotic but a urinary antiseptic originally developed and licensed in the 1960s. This means there is little risk of pathogenic bacteria developing resistance.

- Hiprex is often prescribed alongside antibiotics or on its own.

- If an infection has significantly improved and antibiotics are no longer required on a daily basis, Hiprex is often prescribed as an ongoing treatment to prevent infections reoccurring.

- Hiprex can be taken during pregnancy under clinician management.

The active ingredient is methenamine hippurate. It has antibacterial activity because the methenamine component is broken down to formaldehyde and ammonia in acid urine. By converting to bactericidal formaldehyde it prevents bacterial growth by destroying the proteins and replication abilities within a bacterium

The key to the effectiveness of Hiprex is maintaining concentrated, acid urine so that the main ingredients are activated. If the urine is too dilute and alkaline with a urinary PH of over 6.0, Hiprex will be ineffective. Some people find that taking Hiprex with vitamin C can help to maintain an acid urine balance but this is by personal choice and is not essential to the activation of Hiprex.

In December 2024, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the UK, gave approval to GPs and secondary consultants in updated guidelines for the usage of Hiprex as a prescribed alternate to daily antibiotic prophylaxis for those with recurrent UTI that has not been adequately improved by behavioural and personal hygiene measures, vaginal oestrogen or single-dose daily antibiotic prophylaxis (if any of these have been appropriate and are applicable). They noted that a review of treatment with methenamine hippurate should occur within 6 months, and then every 12 months, or earlier if agreed with the patient.

Localised Oestrogen Therapies

Oestrogen (or estrogen) is needed for the vagina to maintain its natural flora and lubrication. Declining oestrogen levels during the peri and menopausal years leads to changes to vaginal PH increasing alkalinity. This matters because an acidic vaginal environment is protective. It creates a barrier that prevents unhealthy bacteria and yeast from multiplying too quickly and causing infection. Thus a high vaginal pH level — above 4.5 — provides the perfect environment for unhealthy bacteria to grow and these bacteria can transfer from the vagina to the urinary tract causing ongoing infection problems.

A study published in Science Translational Medicine in 2013 47 noted that oestrogen also encourages production of natural antimicrobial substances in the bladder. The hormone also makes the epithelium of the bladder stronger by closing the gaps between cells that line the bladder wall. By “gluing” together the cells of the bladder wall, it helps to prevent bacteria from penetrating to the deeper layers of the wall. Conversely it will also help prevent too many cells from shedding from the top layers of the bladder wall thus preventing exposure of the deeper bladder wall tissues to bacteria. A study carried out by the University of Texas at the European Association of Urology Congress in 2020 48 showed that for some women who took hormone replacement therapies, they had a greater variety of beneficial bacteria in their urine, possibly creating conditions that discourage urinary infections.

For localised oestrogen treatment for the urogenital tract, pessaries have been found to be beneficial. They are entirely topical and will treat the vagina and bladder with minimal systemic absorption although some women still report symptoms despite the low dosage.

Topical oestrogen creams are also available for use in the vagina and vulval area. If skin is highly sensitive, then discuss their usage with the prescribing specialist as the additives within some creams can cause inflammation and burning. A small patch test may be the best option if considering using a cream.

Find Chronic UTI Practitioners in the UK & US

There is no single treatment route for all and symptoms may take time to resolve. However, people can become well again with the appropriate clinical support.

Other factsheets also available:

• Chronic UTI Information for Family and Friends

• Chronic UTI Information Sheet for GPs (written by CUTIC.co.uk)

• An Employer’s guide to Chronic UTI

For further information and support visit:

The Chronic Urinary Tract Infection Campaign

References:

1. Other clinical conditions include kidney stones, kidney infection, menstruation, haemorrhoids, kidney, bladder or urethral cancers, enlargement of the prostrate in men and diabetes.

2. Jepson RG, Williams G, Craig JC. Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 10. Art. No.: CD001321. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001321.pub5.

3. Jepson RG, Mihaljevic L, Craig JC. Cranberries for treating urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1998, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD001322. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001322.

4. Gunnarsson AK, Gunningberg L, Larsson S, Jonsson KB. Cranberry juice concentrate does not significantly decrease the incidence of acquired bacteriuria in female hip fracture patients receiving urine catheter: a double-blind randomized trial. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:137–143. Published 2017 Jan 13. doi:10.2147/CIA.S113597

5. Soto, S. Importance of Biofilms in Urinary Tract Infections: New Therapeutic Approaches. Advances in Biology, Vol. 2014, Article ID 543974, 13 pages, 2014. doi.org/10.1155/2014/543974.

6. Rosen DA, Hooton TM, Stamm WE, Humphrey PA, Hultgren SJ (2007). Detection of Intracellular Bacterial Communities in Human Urinary Tract Infection. PLoS Med 4(12): e329.

7. Thomas K. Wood, Stephen J. Knabel, Brian W. Kwan. Bacterial Persister Cell Formation and Dormancy. Applied and Environmental Microbiology Nov 2013, 79 (23) 7116-7121; DOI: 10.1128/AEM.02636-13

8. Sathiananthamoorthy, S., et al., Reassessment of Routine Midstream Culture in Diagnosis of Urinary Tract Infection. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 2018.

9. Gill, K., et al., A blinded observational cohort study of the microbiological ecology associated with pyuria and overactive bladder symptoms. Int Urogynecol J, 2018.

10. Kass EH. Bacteriuria and the diagnosis of infection in the urinary tract. Arch Intern Med. 1957;100:709-714.

11. Stamm WE, Counts GW, Running KR, Fihn S, Turck M, Holmes KK. Diagnosis of coliform infection in acutely dysuric women. N Engl J Med. 1982;307(8):463-468.

12. Bartlett RC, Treiber N. Clinical significance of mixed bacterial cultures of urine. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 1984;82(3):319-322

13. Latham RH, Wong ES, Larson A, Coyle M, Stamm WE. Laboratory diagnosis of urinary tract infection in ambulatory women. JAMA. 1985;254(23):3333-3336.

14. O’Brien K, Hillier S, Simpson S, et al.(2007) An observational study of empirical antibiotics for adult women with uncomplicated UTI in general practice. J Antimicrob Chemother 59(6):1200–1203.

15. Stamm WE. Quantitative urine cultures revisited. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1984;3(4):279–81.

16. Price TK, Hilt EE, Dune TJ, Mueller ER, Wolfe AJ, Brubaker L. Urine trouble: should we think differently about UTI? Int Urogynecol J. 2017. Epub 2017/12/28. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3528-8. PMID: 29279968.

17. Michael L. Wilson, Loretta Gaido, Laboratory Diagnosis of Urinary Tract Infections in Adult Patients, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 38, Issue 8, 15 April 2004, Pages 1150–1158, https://doi.org/10.1086/383029

18. Khasriya R, Sathiananthamoorthy S, Ismail S, Kelsey M, Wilson M, Rohn JL, et al. Spectrum of bacterial colonization associated with urothelial cells from patients with chronic lower urinary tract symptoms. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(7):2054-62.

19. Thomas-White K, Forster SC, Kumar N, Van Kuiken M, Putonti C, Stares MD, et al. Culturing of female bladder bacteria reveals an interconnected urogenital microbiota. Nature Communications. 2018;9(1):1557. Epub 2018/04/21. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03968-5. PubMed PMID: 29674608; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5908796.

20. Brubaker L, Wolfe AJ. The Female Urinary Microbiota/Microbiome: Clinical and Research Implications. Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2017;8(2). Epub 2017/05/04. doi: 10.5041/rmmj.10292. PubMed PMID: 28467757; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5415361.

21. Price TK, Hilt EE, Dune TJ, Mueller ER, Wolfe AJ, Brubaker L. Urine trouble: should we think differently about UTI? Int Urogynecol J. 2017. Epub 2017/12/28. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3528-8. PMID: 29279968.

22. Price TK, Dune T, Hilt EE, Thomas-White KJ, Kliethermes S, Brincat C, et al. The Clinical Urine Culture: Enhanced Techniques Improve Detection of Clinically Relevant Microorganisms. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(5):1216-22. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00044-16. PMID: 26962083.

23. Hilt EE, McKinley K, Pearce MM, Rosenfeld AB, Zilliox MJ, Mueller ER, et al. Urine is not sterile: use of enhanced urine culture techniques to detect resident bacterial flora in the adult female bladder. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(3):871-6. Epub 2013/12/29. doi: 10.1128/jcm.02876-13. PubMed PMID: 24371246; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3957746.

24. Brubaker L, Nager CW, Richter HE, Visco A, Nygaard I, Barber MD, et al. Urinary bacteria in adult women with urgency urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(9):1179-84. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2325-2. PubMed PMID: PMC4128900.

25. Pearce MM, Hilt EE, Rosenfeld AB, Zilliox MJ, Thomas-White K, Fok C, et al. The female urinary microbiome: a comparison of women with and without urgency urinary incontinence. mBio. 2014;5(4):e01283-14. Epub 2014/07/10. doi: 10.1128 mBio.01283-14. PubMed PMID: 25006228; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc4161260.

26. Wolfe AJ, Toh E, Shibata N, Rong R, Kenton K, Fitzgerald M, et al. Evidence of uncultivated bacteria in the adult female bladder. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50. doi: 10.1128/jcm.05852-11.

27. Sathiananthamoorthy S. PhD The microbiology of chronic lower urinary tract symptoms. UCL: UCL; 2016.

28. Mambatta AK, Jayarajan J, Rashme VL, Harini S, Menon S, Kuppusamy J. Reliability of dipstick assay in predicting urinary tract infection. J Family Med Prim Care. 2015;4(2):265–268. doi:10.4103/2249-4863.154672

29. Khasriya R, Khan S, Lunawat R, Bishara S, Bignal J, Malone-Lee M, et al. The Inadequacy of Urinary Dipstick and Microscopy as Surrogate Markers of Urinary Tract Infection in Urological Outpatients With Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Without Acute Frequency and Dysuria. J Urol, 183 (5) pp. 1843-1847. 10.1016/j.juro.2010.01.008.

30. Kupelian AS, Horsley H, Khasriya R, Amussah RT, Badiani R, Courtney AM, Chandhyoke NS, Riaz U, Savlani K, Moledina M, Montes S, O’Connor D, Visavadia R, Kelsey M, Rohn JL, Malone-Lee J. Discrediting microscopic pyuria and leucocyte esterase as diagnostic surrogates for infection in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms: results from a clinical and laboratory evaluation. BJU Int. 2013;112(2):231-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11694.x. PubMed PMID: 23305196.

31. Theodoros A. Kanellopoulos, Paul J. Vassilakos, Marinos Kantzis, Aikaterini Ellina, Fevronia Kolonitsiou, Dimitris A. Papanastasiou. Low bacterial count urinary tract infections in infants and young children. Eur J Pediatr (2005) 164: 355–361 DOI 10.1007/s00431-005-1632-0

32. Kjell Tullus, Low urinary bacterial counts: do they count? Pediatr Nephrol (2016) 31:171–174 DOI 10.1007/s00467-015-3227-y

33. Price et al. The Clinical Urine Culture: Enhanced Techniques Improve Detection of Clinically Relevant Microorganisms. Ibid

34. Wolfe et al. Ibid

35. Kogan M, I, Naboka Y, L, Ibishev K, S, Gudima I, A, Naber K, G: Human Urine Is Not Sterile – Shift of Paradigm. Urol Int 2015;94:445-452. doi: 10.1159/000369631

36. Hilt, E.E., McKinley, K., Pearce, M., Rosenfeld, A., Zilliox, M., Mueller, E., Brubaker, L., Gai, X., Wolfe, A.J., Schreckenberger, P. Urine Is Not Sterile: Use of Enhanced Urine Culture Techniques To Detect Resident Bacterial Flora in the Adult Female Bladder. J Clin Microbiol Feb 2014, 52 (3) 871-876; DOI: 10.1128/JCM.02876-13

37. White, K., Brady, M., Wolfe, A.J. et al. The Bladder Is Not Sterile: History and Current Discoveries on the Urinary Microbiome. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep. (2016) 11: 18.

38. Bao, Y., Al, K., Chanyi, R., Whiteside, S., Dewar, M., Razvi, H., Reid, G., Burton, J.. Questions and challenges associated with studying the microbiome of the urinary tract. Ann Transl Med., 5, Jan. 2017.

39. Soto, S. Importance of Biofilms in Urinary Tract Infections: New Therapeutic Approaches. Advances in Biology, Vol. 2014, Article ID 543974, 13 pages, 2014. doi.org/10.1155/2014/543974.

40. Mulvey MA, Schilling JD, Martinez JJ, Hultgren SJ. Bad bugs and beleaguered bladders: interplay between uropathogenic Escherichia coli and innate host defenses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000 Aug 1;97(16):8829-35.

41. Scott VC, Haake DA, Churchill BM, Justice SS, Kim JH. Intracellular Bacterial Communities: A Potential Etiology for Chronic Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. Urology. 2015;86(3):425–431. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2015.04.002

42. Swamy, S., Barcella, W., De Iorio, M., Gill, K., Rajvinder, K., Kupelian, A., Rohn, J., Malone-Lee, J. Recalcitrant chronic bladder pain and recurrent cystitis but negative urinalysis. What should we do? Int Urogynecol J (2018) 29: 1035

43. Lebeaux D, Ghigo JM, Beloin C. Biofilm-Related Infections: Bridging the Gap between Clinical Management and Fundamental Aspects of Recalcitrance toward Antibiotics. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2014 Sep;78(3):510-43. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00013-14.

44. Swamy, S., Barcella, W., De Iorio, M., Gill, K., Rajvinder, K., Kupelian, A., Rohn, J., Malone-Lee, J. Recalcitrant chronic bladder pain and recurrent cystitis but negative urinalysis. What should we do? Int Urogynecol J (2018) 29: 1035

45. Swamy, S., Kupelian, A., Rajvinder, K., Dharmasena, D., Toteva, H., Dehpour, T., Collins, L., Rohn, J., Malone-Lee, J. Cross-over data supporting long-term antibiotic treatment in patients with painful lower urinary tract symptoms, pyuria and negative urinalysis Int Urogynecol J (2018) IUJO-D-18-00488R1

46. Swamy, S., Barcella, W., De Iorio, M. et al. Recalcitrant chronic bladder pain and recurrent cystitis but negative urinalysis: What should we do?. Int Urogynecol J 29, 1035–1043 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3569-7

47. Petra Lüthje et a. Estrogen Supports Urothelial Defense Mechanisms.Sci. Transl. Med.5,190ra80-190ra80(2013).DOI:10.1126/scitranslmed.3005574

48. Neugent ML, Kumar A, Hulyalkar NV, Lutz KC, Nguyen VH, Fuentes JL, Zhang C, Nguyen A, Sharon BM, Kuprasertkul A, Arute AP, Ebrahimzadeh T, Natesan N, Xing C, Shulaev V, Li Q, Zimmern PE, Palmer KL, De Nisco NJ. Recurrent urinary tract infection and estrogen shape the taxonomic ecology and function of the postmenopausal urogenital microbiome. Cell Rep Med. 2022 Oct 18;3(10):100753. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100753. Epub 2022 Sep 30. PMID: 36182683; PMCID: PMC9588997.